2016 was the year of Fake News. Let’s make 2017 the year that one of those fake stories finally goes away.

Your family’s surname was not changed at Ellis Island.[1]

You know the story. It goes something like this:

- Carl? That’s not Russian.

- The clerk at Ellis Island named your family after his son.

- It was “German Day” at Ellis Island and that’s how your ancestors were called Carl.

- The name was too long and ended in –sky or –itz or something and the clerk shortened it to make it easier to write.

There are hundreds of variations of this story. None of them are true.

Nope. No. Nein. Nem. Nu. Nie. Нет. קיין .

[2]

Language plays an important role in this myth. Many of the people who purport the story of the name change have ancestors who emigrated from a country that used a different alphabet, or had different letters, or used diacritical marks to distinguish pronunciation. An immigrant from the Russian Empire might know how to spell their surname using Cyrillic or Hebrew letters, and that name had to be transliterated into the Latin alphabet. A Pole with the letter Ł in a name would expect a “W” sound, not “L.” Umlauts and other diacritic marks from German, Hungarian, Czech and other languages do not neatly transliterate.

The creation of the ship’s manifests, or passenger lists, took place in Europe. The clerk was at the ticket agency. A copy of that list was sent with the ship’s captain to be presented at the port of entry. Sometimes a copy of that list remained at the port of embarkation.

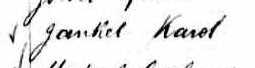

On 29 May 1900, the Lake Huron set sail for North America from Liverpool, bound for the Port of Quebec in Montreal. An “Outwards Passenger List” was cre ated, and kept in England. A similar version of the list went with the ship, and can be found in the Library Archives Canada collections. Both lists have the same version of the surname of an immigrant from Russia: KAROL.

ated, and kept in England. A similar version of the list went with the ship, and can be found in the Library Archives Canada collections. Both lists have the same version of the surname of an immigrant from Russia: KAROL.

Wait. Montreal? That raises another big factor in the myth. Did the family arrive at Ellis Island? What about its precursor, Castle Garden? Or Montreal? Or Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, New Orleans or Galveston?

The final destination of this passenger was Boston, not Montreal, so another list is associated with the travel – on a form required by the US Government. Called a List or Manifest of Alien Immigrants for the Commissioner of Immigration, it too, was created prior to arrival. The fine print on the document illustrates that point:

Required by the regulations of the Secretary of the Treasury of the United States, under Act of Congress approved March 3, 1893, to be delivered to the Commissioner of Immigration by the Commanding officer of any vessel having such passengers on board upon arrival at….

In this case, the list was used when the passengers prepared to cross the border from Canada to the United States. Again, the surname of the passenger was spelled KAROL.

After a few years of living with his sister-in-law’s family in Boston, this immigrant moved to St. Louis. He earned enough money to pay for the passage of his wife and children. They boarded the Pennsylvania in Hamburg and traveled to the Port of New York, arriving at Ellis Island on 22 Jan 1905. The surname on the manifest read CARROL.

I can hear the myth-lovers: “that’s it – it was Irish day at Ellis Island, and that is why they changed KAROL to CARROL.”

No. Nope. Nein. Nem. Nu. Nie. Нет. קיין. Or as the Irish might say, Ní féidir.

Like the UK Outwards Passenger List, immigrants leaving from Hamburg were noted on passenger lists; lists stored at the Staatsarchiv Hamburg in Germany. The Hamburg lists match the Ellis Island passenger manifest, surname spelled CARROL.

Sometime between arriving in Boston in 1900 and moving to St. Louis about 1904, Jankel KAROL changed the spelling of his name to Jankel CARROL. When he purchased the steamship tickets for his family, the manifest listed his name and address as: Jankel CARROL, 814 Biddle Street in St. Louis, nearly an exact match to the listing in the City Directory for Jacob CARROL at 814 Biddle Street. Jankel is the Yiddish nickname for Yaacov, the Hebrew version of Jacob. It’s not just surnames that change as families Americanized.![]()

The surname CARROL changed one additional time, to CARL, before 1910, in St. Louis, some 950 miles from Ellis Island. Why? That cannot be answered. Som e educated guesses could be made, but those guesses become stories, and those stories run the danger of feeding the myth.

e educated guesses could be made, but those guesses become stories, and those stories run the danger of feeding the myth.

Let’s recap:

- Passenger lists and manifests were created by ticket agents in Europe;

- Alphabets and pronunciation play a role in spelling;

- Some ports of departure kept copies of passenger lists and the names from those lists match the names on lists at the port of entry; and

- Not all immigrants arrived at Ellis Island!

Still not convinced? Here are some additional resources discussing the myth of the Ellis Island name change:

Why Your Family Name Was Not Changed at Ellis Island (and One That Was)

Philip Sutton, Librarian, New York Public Library

American Names: Declaring Independence and Examples of Name Changes from the National Archives

Marian L. Smith, Senior Historian, U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service

The Name Remains the Same

Robin Meltzer, Jewish Genealogy Society of Greater Washington

[1]If only Snopes was on the case.

[2] English slang, Italian & Spanish, German, Hungarian, Romanian, Polish, Russian, Yiddish.