As a young reader, I loved the book From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler by E.L. Konisburg, and the novel came to mind the past few days as I sought out a Civil War Pension file.

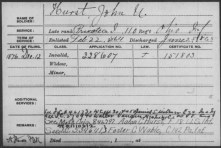

It started out as a simple request – could I locate the file and scan the contents for a researcher in Texas? He provided me with the T288 index card for Walter Vaughn, who had been a member of the 74th Indiana Infantry, Company H, and the 1st Regiment U. S. Veteran Volunteer Engineers, Company C, during the Civil War.

I took the application and certificate numbers from the index card, which dated to 1880, when Walter Vaughn applied for an invalid pension, and filed a search request at the National Archives. Usually, retrieval from the stacks takes about an hour. I went up to the reading room, but received the dreaded white “return request” slip. The file was not located. My mistake, I should have also checked the T289 organizational index for the same soldier.

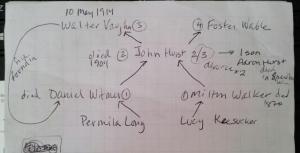

Pulling up the T289 index card for Walter Vaughn began what one NARA staffer dubbed, “a rabbit hole” of names, dates and files. On this card, the clerk, writing almost 100 years ago, wrote to also reference the files of John U. Hurst of Ohio and Daniel S. Witmer of Indiana. I emailed the researcher, asking if he wanted me to continue, and if he knew either of these additional surnames. He knew the surname Witmer as the maiden name of Walter Vaughn’s wife, Permila.

A staffer helped me as I pulled up information on the new names, which resulted in even more “see also” notations: Foster Wable and Aaron Hurst. Who were all these men and how did they all connect? Papers were scattered across the staffer’s desk, and I sketched a flow chart to see if that provided any clarity. Meanwhile, two additional staffers joined in the discussion. One noted that on Aaron Hurst’s card was the name of his mother: Lucy Wable. Lucy? I thought we were looking for Permila! I assembled a small stack of file requests, and the staffers made me promise to give them the full report of what I found.

A staffer helped me as I pulled up information on the new names, which resulted in even more “see also” notations: Foster Wable and Aaron Hurst. Who were all these men and how did they all connect? Papers were scattered across the staffer’s desk, and I sketched a flow chart to see if that provided any clarity. Meanwhile, two additional staffers joined in the discussion. One noted that on Aaron Hurst’s card was the name of his mother: Lucy Wable. Lucy? I thought we were looking for Permila! I assembled a small stack of file requests, and the staffers made me promise to give them the full report of what I found.

Based on the flow chart and dates on the index cards, I guessed that the answer might be found in Foster Wable’s file. The file was at least three inches thick. I dug in – pages and pages on Foster Wable’s application for a pension, even more pages on his wife Lucy’s application for a widow’s pension, and yet even more pages on Lucy’s application for her son Aaron Hurst’s benefits. Lucy’s marital history partially explained things: Foster Wable was her fourth marriage and third husband. Her second marriage was to John Hurst, and they had a son, Aaron. John and Lucy divorced, then remarried, then divorced again. I found a touching note from the nurse who cared for Aaron Hurst as he lay dying in the Philippines during the Spanish-American War, but not one mention of Walter Vaughn or Permila. The filed turned out to be a total red herring.

Next up, Daniel Witmer’s file, another thick set of papers. Again, multiple pages of applications for pension, but most of it was focused on Permila J. Long and her widow pension applications, and rejections. Permila married Daniel Witmer in 1866; he died in 1892. She married John Hurst in 1900; he died in 1904. Finally, she married Walter Vaughn.  This explained the connections between the women and the men, and I found Walter Vaughn’s pension files after all the paperwork for Daniel Witmer. This allowed me to complete my client’s request, but it didn’t satisfy my curiousity – why was Walter Vaughn filed with Daniel Witmer? If there was a widow’s pension, it would have been filed as such, but these files were for soldier’s pensions.

This explained the connections between the women and the men, and I found Walter Vaughn’s pension files after all the paperwork for Daniel Witmer. This allowed me to complete my client’s request, but it didn’t satisfy my curiousity – why was Walter Vaughn filed with Daniel Witmer? If there was a widow’s pension, it would have been filed as such, but these files were for soldier’s pensions.

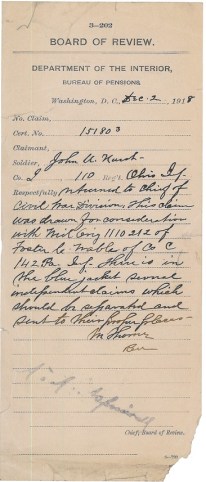

I had one more file to go, John U. Hurst. Ultimately, I did locate the “Rosetta stone” for the files, a piece of paper in John Hurst’s file, with the notation from a clerk written on 2 December 1918:

There is in the blue jacket several independent claims which should be separated and sent to their proper places.